It may surprise people outside of Vermont to hear that the Green Mountain state has a housing crisis. We are used to thinking of housing affordability being a problem mainly in urban areas on the coasts. Vermont doesn’t fit either of those descriptions. And yet, housing is the single greatest challenge Vermont faces today. Vermont’s legislature is currently in session and housing is one of the hottest topics. My family and I moved here in August 2019 and were initially very excited about it. We love winter, skiing, and hiking. For the last two years or so, we have been looking to buy a house here, to no avail. And we feel terrible for people who make less money than we do. If we are struggling to find something we can afford, how much worse must it be for them. And why does Vermont have such a bad housing crisis in the first place? I’m a professor in the Political Science department and the International Politics and Econmics program at Middlebury College and I wrote an academic book on regulatory trade barriers. I’m naturally interested in the intersection of regulation and markets so I started investigating this question. For the last year or so, I have been talking to housing advocates, elected officials, and everyday Vermonters about housing, and intermittently tweeting about Vermont’s housing problems. I think Vermonters deserve a full explanation of exactly how we as a state got here and what our options are to get out of this mess. I also hope that this explanation proves useful to people in other states as well.

A Problem That Touches Everything

If you look at affordability as defined by the difference in what people make and what they need to afford a one-bedroom rental, the Burlington area (the only small metro area in the state) ranks 6th most expensive out of 119 small metro areas in the country. Only Atlantic City, New Jersey and four small metros in California are worse. The median one bedroom in Burlington rents for $1,345 a month versus $701, $753, and $908 in Eau Claire Wisconsin, Kalamazoo Michigan, and Gainesville Florida respectively. The vacancy rate in Chittenden County is 0.4%. 4-8% is generally what is considered healthy. A quarter of Vermont renters spend more than half of their income on rent and another quarter spend between 30 and 50 percent.

According to a recent report from the Department of Housing and Urban Development, Vermont ranks second behind only California in homelessness as a percentage of the population. As a percentage of the population, we have five times as much homelessness as the state of Texas. Other states, like Florida, have reduced homelessness since 2007 by more than 40 percent. In that time, Vermont’s has increased by 168%, more than any other state.

It is not just the homeless who suffer. Because there is an acute shortage of missing middle housing, seniors who would like to downsize can’t and so that further contributes to the state’s housing gridlock. First-time homebuyers in the working class, middle class, and even professional class find themselves with few if any options. Homes for sale here are all some combination of tiny, very old, in need of serious renovation, or astronomically priced. The cover image that I used for this, from the last part of Seven Days exceptionally good 12-part series on Vermont’s housing crisis, gets at how first time homebuyers feel here. It’s like “oh you don’t have a bajillion dollars, well then I guess you can’t come in. Go somewhere else.”

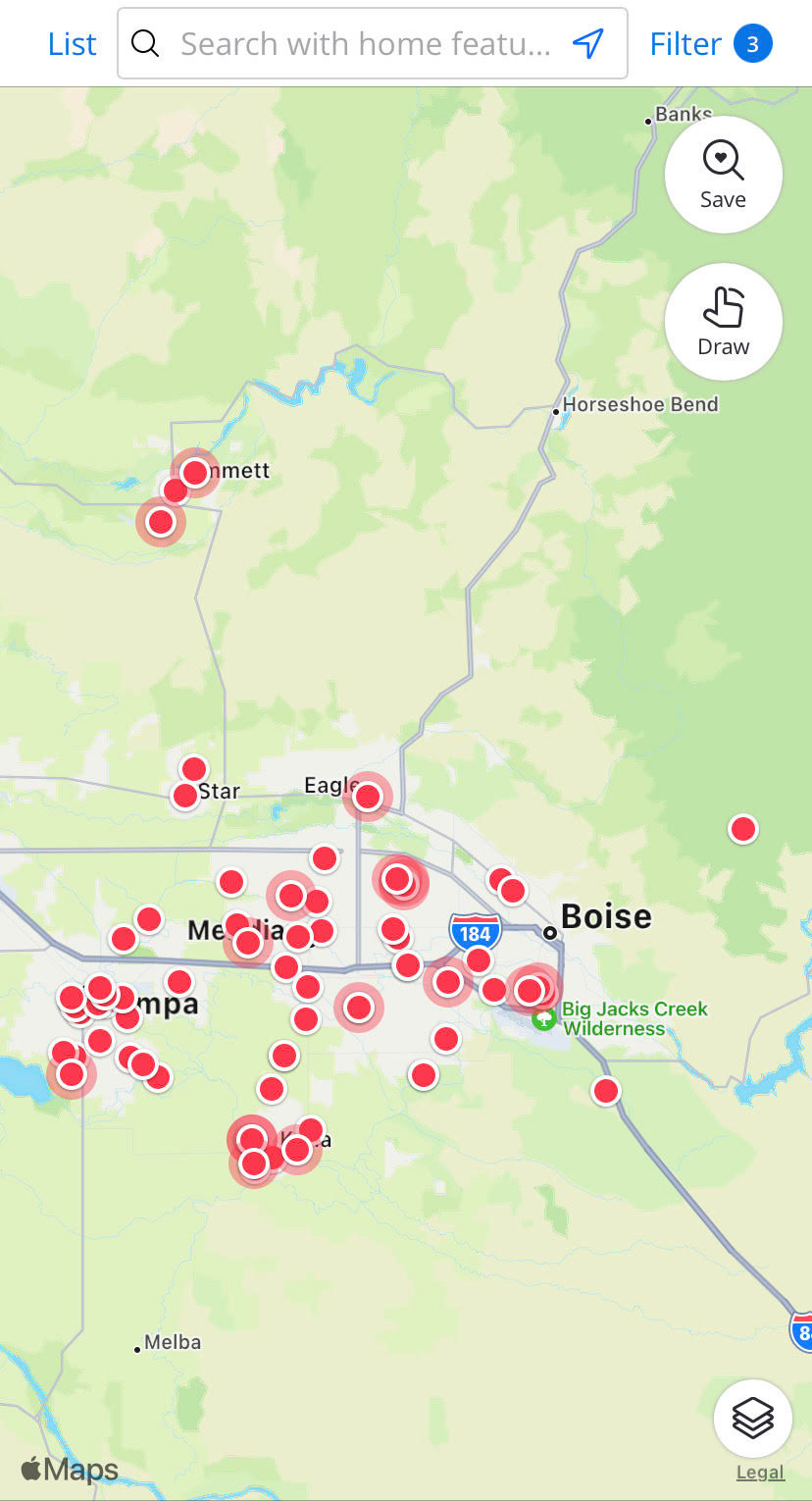

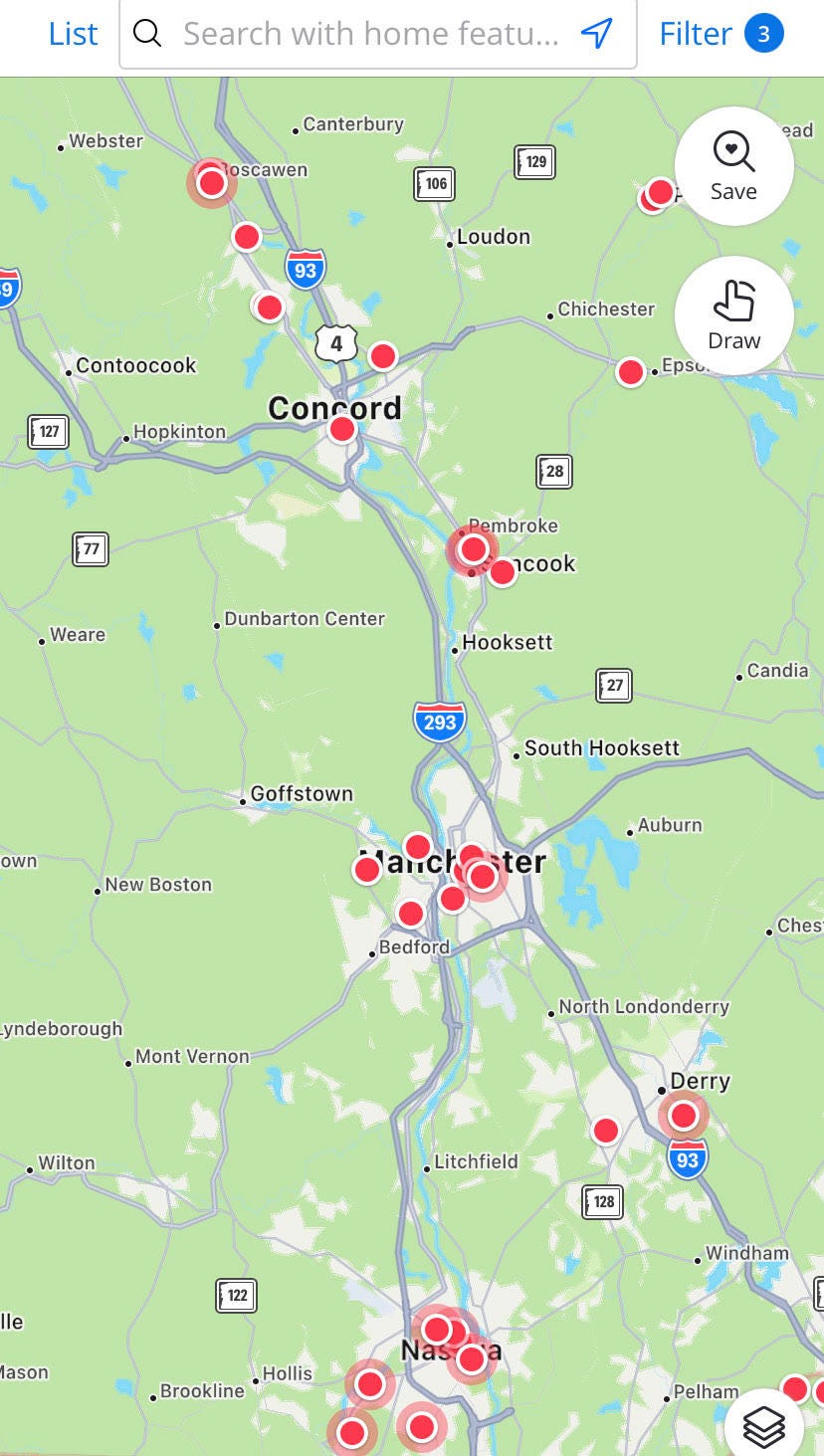

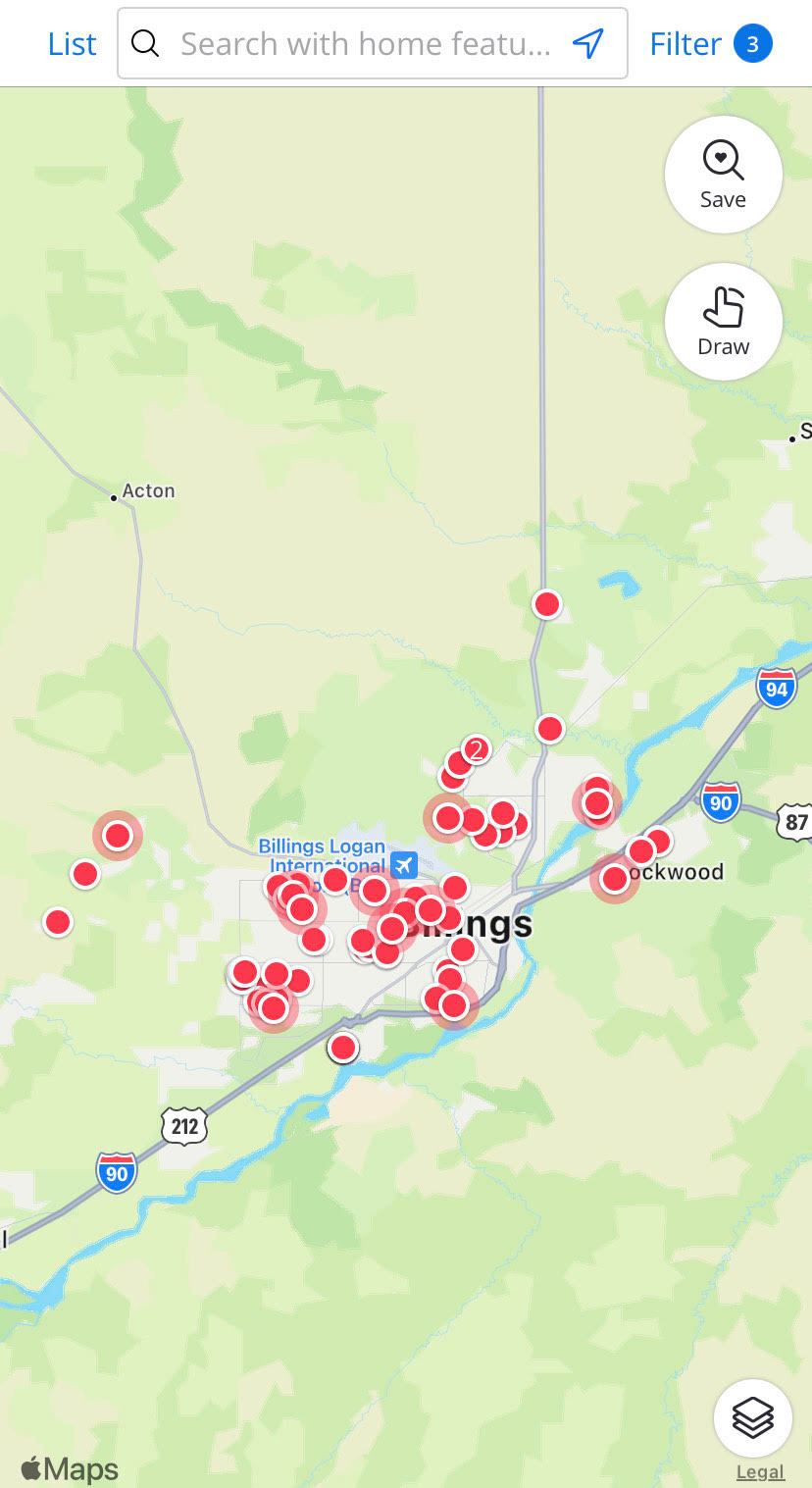

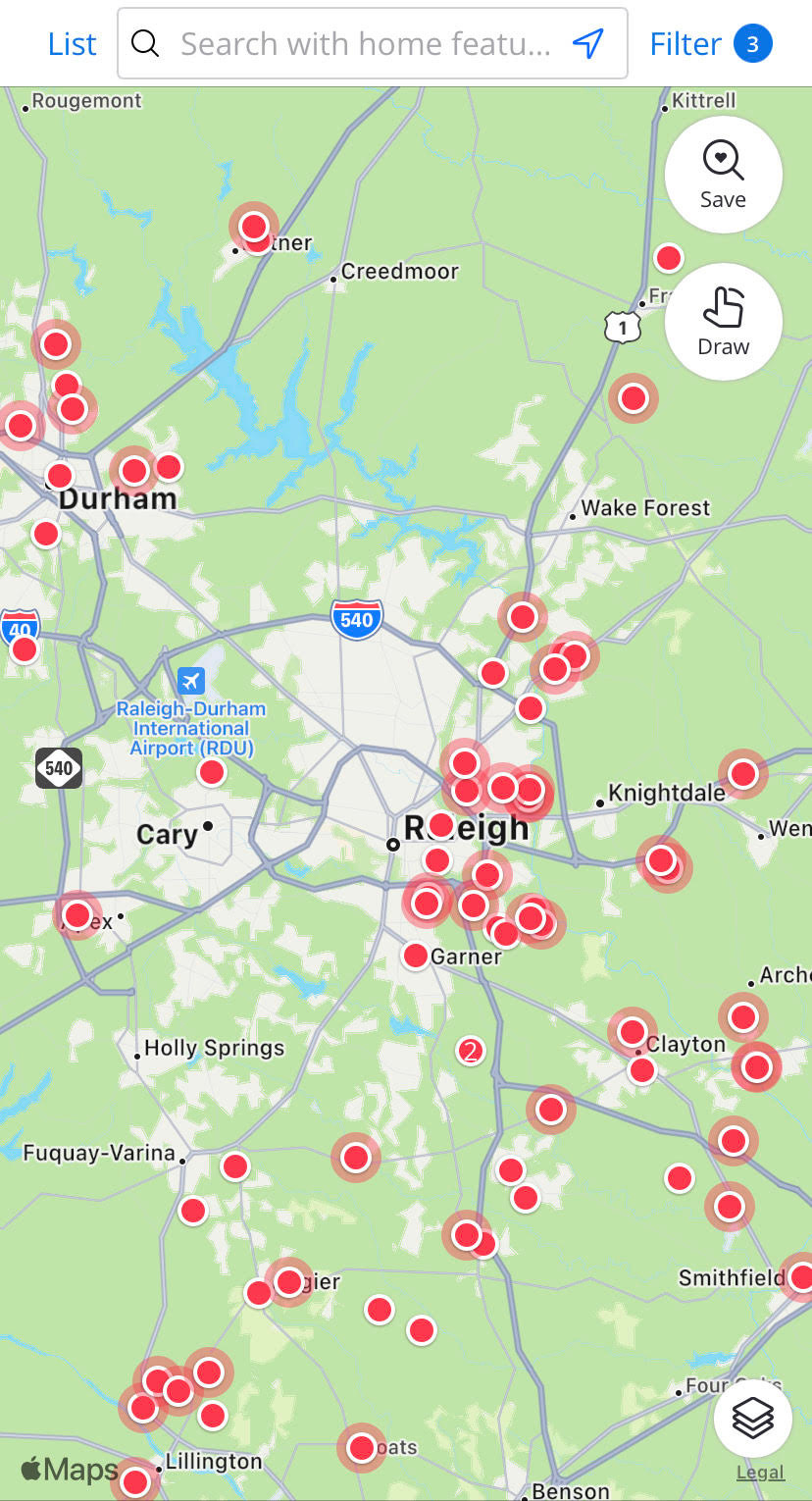

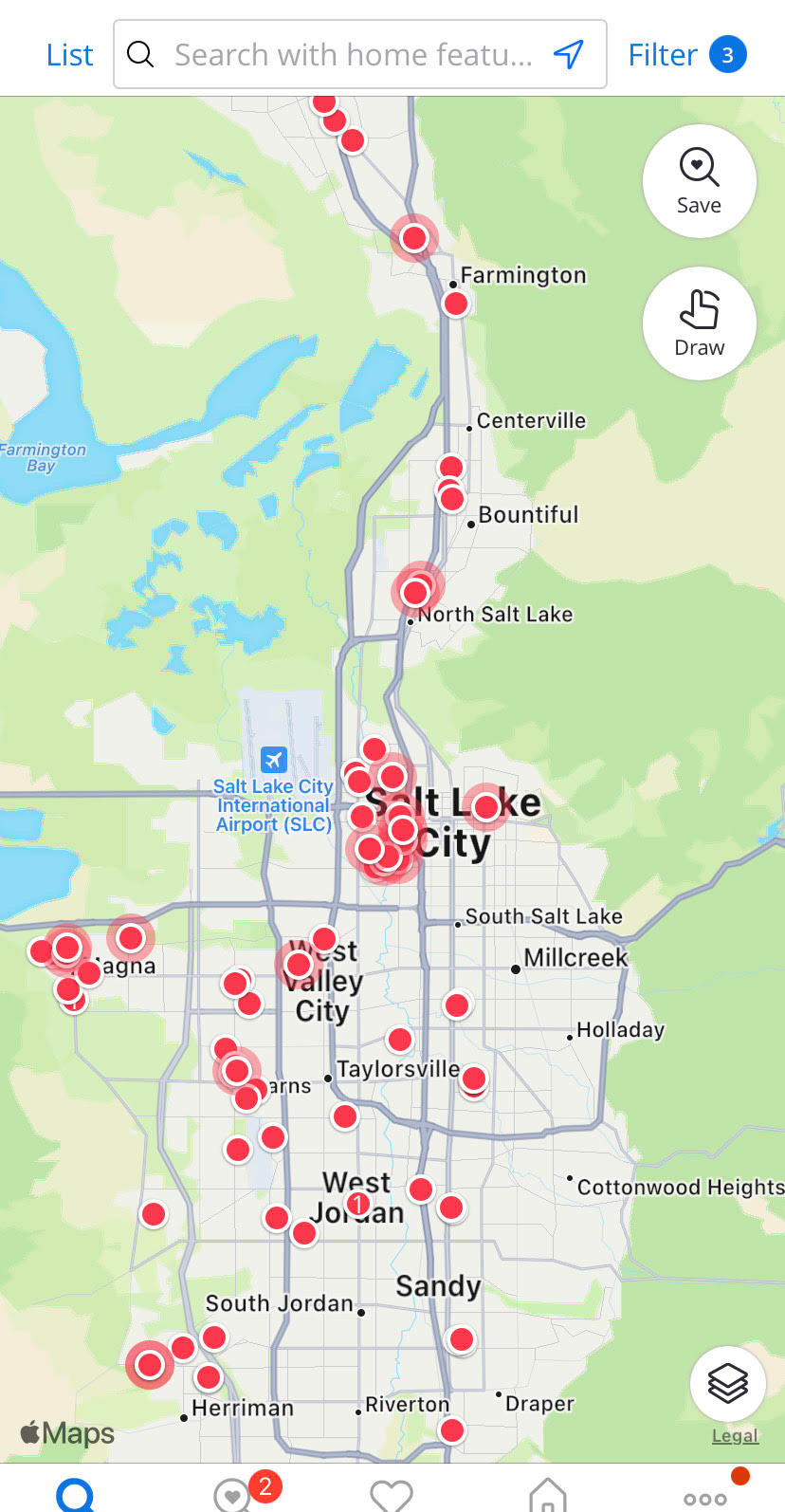

Perhaps the easiest way to see the problem visually is to take a look at Zillow. Here are some maps of all of the 3-bedroom homes (single family houses, apartments, townhouses, or condos) available for $400,000 or less in the areas in and around Billings Montana, Boise Idaho, southern New Hampshire, Raleigh North Carolina, Salt Lake City Utah, and Burlington Vermont. See all the red dots in those other places. See the no red dots in the Burlington area. When Vermont’s political leadership asks themselves why so many young people leave, these red dots (and lack thereof in VT) should be seared into their minds. People cannot live here if there is nowhere for them to live. When young people leave Vermont, it is usually not because they hate Vermont. It because they are voting with their feet in favor of places with reasonably priced housing.

The condo complex that I live in has a good number of middle-class families with young kids, most of whom would like to be homeowners, none of whom can afford to be. Just in the last year, I’ve seen two families (both with kids) leave Vermont for states with cheaper housing. I have a four-year-old. At little kids’ birthday parties, among the parents who are not already homeowners, there is a lot of talk of leaving, preparing to leave, and wanting to leave. The family of at least one of my daughter’s classmates from last year left the state about six months ago and I know for a fact that it was about housing costs. Seven Days profiled young Vermonters leaving because of housing costs. One, who works as an electrician and a bartender, said "We're moving out of state in order to start a proper life and save money for retirement.. Vermont doesn't seem — at least currently or in the near future — to be a place where we can do that."

Losing young people, in large part because housing is so expensive, is one of the main reasons that Vermont is getting older. As a state government reports notes:

“The year 2017 marked the first time that Vermont had as many seniors (65+) as children (<18). Just two decades earlier, children outnumbered seniors by more than two to one. Over the coming decade, seniors will outnumber children by an increasing margin as younger baby boomers reach retirement age (Figure 3). Meanwhile, the number of children and working-age adults is projected to continue dropping. By 2030, just 47% of Vermonters will be between the ages of 25 and 64, down from 54% in both 2000 and 2010.”

These housing problems cause all kinds of other problems too.

According to an analysis by the Washington Post, Vermont ranks dead last in losing college students after graduation. When 100 college students graduate in Colorado, not only do they keep those 100 on average they gain 41 more. Georgia gains 15 more. By contrast, when 100 college students graduate in Vermont, we lose 58 of them. In part because people who work in childcare cannot afford to live here, relative to local wages, Vermont has the most expensive childcare in the country at 12.8% of a married couple’s income. In Oregon, it’s only 9%. In Mississippi, it’s just 6.7%. Because Vermont’s population is aging, the tax base continues to shrink even while tax rates continue to climb; Vermont now has the 4th highest overall tax burden in the country. Because the tax base is shrinking, Vermont cannot afford to support important services. That’s why Vermont now was the most expensive in-state college tuition of all 50 states, at more than $30,000 per year. In Florida, Wyoming, and Utah, it’s less than half that.

Workers who accept jobs in Vermont are increasingly backtracking and turning those jobs down because they cannot find adequate housing, and this problem has become particularly bad among the kinds of specialized skills workforce recruits that Vermont is in especially desperate need of. One employer said “Last year, we approached a tipping-point moment, where we were starting to see newly graduated nurses accept our offers of employment, and then they wouldn't be able to secure housing and they would withdraw their acceptance." An orthopedic trauma nurse at Dartmouth-Hitchcock with two kids found herself couch surfing for a while because she had nowhere to stay; she said “It's very, very humbling, more humbling than getting divorced. I don't know what I did wrong. I'm very fiscally responsible and save and do all that stuff." OnLogic, a South Burlington-based company, has shifted more of its work to its Cary, North Carolina location because it is easier to find workers there because housing is more affordable there.

If we had better housing policy, we could attract young people the way Colorado does, keep college costs down the way Utah does, keep childcare costs down the way Oregon does, keep taxes down the way Tennessee does, and keep rent down the way lots of places do. But we don’t. I understand that many Vermonters want to keep Vermont weird. I don’t know what to say to that other than to say that weirdly expensive housing, weirdly high homelessness, a weirdly high rate of losing college graduates, weirdly expensive childcare, weirdly expensive college tuition, and weirdly high taxes are not the ways in which you should want your state to be weird.

How did we get here? As with most other problems of this magnitude, there are a number of overlapping factors. Let’s get into them.

A Culture of Change-Resistance and Communitarian Thinking

People may not realize this because Vermont is such a solidly blue state today, but it was once amongst the most Republican states. It was one of only of only two states (Maine was the other) that never voted for FDR. I was speaking with former Governor Jim Douglas (his office at Middlebury College is next to mine) and he explained to me that Vermont has a long history of voters being quite cautious about things and this helps explain that Republican streak for most of the 20th century and why Vermont so rarely ousts incumbents. What Governor Douglas diplomatically called caution others I have spoken to have more bluntly called change-resistance. For better or for worse, Vermont has resisted modernity about as strongly as anywhere in the United States possibly could. This is not always a bad thing. I rather like that the state has a ban on billboards. Some of the tourist draw of Vermont is no doubt because it can seem like a place from another time. Particularly in a world that can occasionally be a little loud and a little pressured, a weekend into verdant landscapes and zero urgency has a certain attraction. Still, that resistance to change has its costs. It’s one of the core ideational pillars that undergirds the state’s anti-development, anti-housing politics.

To understand how deep and how old this resistance to change is, it helps to know the story of Romaine Tenney. In the early 1960s, the government was building Interstates 91 and 89, the first two interstate highways in Vermont. “The highway would rescue Vermont–take the state “out of the sticks” and put it “right in the economic mainstream of the country,” said Elbert Moulton, the state’s economic development chief under four governors.” Except Romaine Tenney’s farm was in the way. Tenney would not accept compensation for the property and, even once it was taken by eminent domain, refused to move. On what the authorities said would be his final night on the farm, Tenney set fire to the sheds, barns, and house, with himself inside. He burned himself to death rather than leave his land. “The suicide of the old Yankee farmer was national news, picked up by papers from New York to Los Angeles. Romaine rapidly became a symbol: the stubborn Yankee, the farmer who wouldn’t be bought, the man who chose his own death. He personified Vermont.” It’s a tragic story. Truly. Even people who accept that the highway was necessary can’t help but be saddened by any person dying in such a way. But it does go to show you how deeply ingrained opposition to encroaching modernity is in some parts of the Vermont spirit. This change resistance continues through to today. There’s a joke I heard from a longtime Vermonter that goes like this: “How many Vermonters does it take to change a lightbulb? Trick question, no one’s allowed to change anything in Vermont.” Even Bill McKibben, probably the most famous environmentalist in Vermont, said “I love Vermont dearly and admire its conservation ethic but there are moments, faced with a global crisis, when it feels like the state motto should be ‘Don't change a thing until I die.’”

A few years before Romaine Tenney’s tragic demise, in 1962, the Supreme Court established the “one person, one vote” standard in Baker v. Carr. While the case was about Tennessee’s Jim Crow attempts to reduce Black citizens’ political voice, it also had a profound impact on Vermont. The state constitution from way back in 1791 guaranteed each town, no matter how small or large, one representative in the lower chamber of the Vermont legislature so Stratton (pop. 24) had as much representation as Burlington (pop. 35,531). Baker v. Carr meant the state could no longer do that. Note though that in the Vermont tradition each town had been given a representative, and that counties have virtually no power in Vermont. Meanwhile, Vermont maintained a “Meeting Day” culture that survives to this day. As is well known to all Vermonters but is to some degree unheard of outside of the state, every year Vermonters gather in their towns for Town Meeting Day where the most important business of the year for the town is decided (this year’s is coming up on March 7th). Meeting Day itself spawns a whole Meeting Day culture that creates a broad set of very communitarian norms and a strong sense of place. You can hear that sense of place in productions like the Rumble Strip podcast.

As with the resistance to change, that has pros and cons. There’s no denying that there is something Tocquevillian about the practice, and longtime Vermonters seem to take great pride in it, and there is a good case to be made that it contributes to social trust and social cohesion. That can have real world benefits. During COVID, vaccines, masking, and social distancing became much less politicized in Vermont than elsewhere and we had fewer cases and fewer deaths than just about anywhere else despite having an older, more vulnerable population. Earlier I mentioned some of the ways in which Vermont is weird that are not so great. Well, during the pandemic, we were weird in a way that was exceptionally good, best in the nation in my view. Our elected leaders like Governor Scott deserve a lot of credit for that but a lot of that success, I think, can be traced to this more communitarian spirit.

All that said, communitarianism can go too far and it is a contributing factor in our housing crisis. It turns each town into what amounts to a zip code-sized HOA, with busybodies genuinely believing that they should have a say on anything they can see, not just from their porch, but anything they can see while driving around. Given the topography of the place, what you can see while driving around often encompasses just about everything. Not only that, but because towns have all the power, changes that will have relatively small local costs but relatively larger benefits for the wider geographic community aren’t seen that way. They are seen only through the small local costs and not through the county-wide or regional benefit. In addition that, while this meeting day culture is in some sense democratic, it can also be profoundly inequitable in how it treats people who are time-rich versus people who are time-poor. Money is not the only form of inequality. Some people have a lot of time on their hands while others have almost none. People who have a lot of time can spend some of that going to meetings while people with less time cannot. Who typically has the time available to go to all of these specialized meetings? Recently retired people. Who has almost no time and ability to go to these meetings? Parents with young kids. A politics that is based on who can show up to a meeting is going to systematically favor retirees over young families.

When you combine the change-resistance to the norm of “I should have a say in anything I can see while I drive around because it’s my community” to the decision-making being situated at the super-local level to a political system that favors retirees (who typically own their homes) over young families (who are typically the ones trying to buy), that’s a recipe for anti-development politics. But it doesn’t stop there.

Hippies and Act 250

Vermont had a long history of utopian, communal, religious communities. Joseph Smith, founder of the Mormon faith, was even born in Vermont. It also had a tradition of welcoming outsiders who wanted to get away from modernity. Rudyard Kipling wrote The Jungle Book while on a writing retreat in Vermont. So, in some ways it shouldn’t have been terribly surprising that by the time we get to the late 1960s and early 1970s, Vermont became something of a hotbed for hippie and communal living. And there weren’t just a few of them. By 1970, there were more than 35,000 hippies in Vermont. Relative to Vermont’s 1950s population, lots of new people, many of them environmentalists, hippies, or back-to-the-land types came to Vermont. This was when today’s most famous Vermonter, Bernie Sanders, arrived from Brooklyn.

By the mid-1970s, “although the flood of communes had subsided, what it left behind was a legacy of commitments to alternative energy, alternative schools, art collectives, community gardens, farmers markets” etc.

This too contributed to much of the background ideology you can see in today’s Vermont. Significant parts of it really do have something of a counter-cultural vibe to them. It also created a certain path dependency. People who were attracted to that kind of aesthetic were more likely to move here and people who didn’t like that were less likely to move here.

This had implications for housing politics. What do hippies hate even more than showers? Suburbs, that’s what, and they weren’t going to welcome any new suburbs here. Think about it, they ran away to Vermont to get away from normal suburban America which they disliked for all sorts of reasons. The absolute last thing they wanted was for normal suburban America to follow them here. The latent hippie sentiment that suburbs are in some sense bad is one of the drivers of anti-suburban, anti-development sentiment today. One housing opponent in South Burlington even used lyrics from the 1963 Pete Seeger song lyrics “Little Boxes” to decry a new housing development, making fun of those houses and the people who live in them as “ticky-tacky.” Another opponent of housing in South Burlington who is a former City Councillor argued that there shouldn’t be any new housing in South Burlington so that the town can be fully self-sufficient in food production. It is hard to fully convey just how economically nonsensical it is to want to implement North Korean-style Juche in food rather than allow development but there it is.

What else besides suburbs do hippies strongly dislike? Capitalism. Even today, when you talk to some Vermonters about housing, you can hear the hippie-infused anti-capitalism in their rhetoric. One of the biggest complaints that you’ll hear about new housing is that some developer will make a profit. Why profiting from providing housing, a necessary good, is supposed to be offensive I have yet to figure out. Seriously. If there is anything you should be able to make money doing, it should be providing other people with housing. Developers should be seen as no different from grocers or doctors in that regard.

Still, even if you’re kind of an anti-capitalist anti-suburb hippie, you need a place to live. So as this generation got into their prime home buying years, they were able to convince towns to allow some new housing to be developed. Housing construction rates were quite healthy during the 70s and much of the 1980s. You can see the issue that’s brewing though. There were a bunch of residents who wanted housing for themselves but were quite wary of “too much development” that might somehow spoil this environmentalist Eden. This is exactly what happened. We used to build more housing at a slow but steady pace. Now we build almost nothing at all.

All of this was happening amidst an environmentalism that I’ve described elsewhere as pastoralist rather than futurist and as:

“more committed to keeping things the way they are, often hostile to economic growth and markets, more eager to attach environmental concerns to other left-wing causes, and more skeptical of technological solutions to climate change. For them, the cause of environmental degradation is the greed of consumer capitalism and so the answer to that degradation is to convince people to want less. They want climate action to be rooted in an ethos of solidarity, sustainability, localism, and perhaps a touch of tie-dye. This form of environmentalism is first and foremost about stopping commercial actors from doing environmentally damaging activities. The central image is an activist standing in front of a bulldozer. You can see this Pastoralism in cultural productions like Fern Gully, Captain Planet, and Avatar. Even today, the Pastoralists’ anti-development sensibilities and activist orientation infuses much of the environmental advocacy world; it unites the Sierra Club with the Sunrise Movement, the Extinction Rebellion with King Charles.”

That pastoralist sentiment took institutional form in Vermont’s Act 250, enacted in 1970. Act 250 is deliberately designed to throttle development. As VPR’s John Dillon explains, Act 250 “was written in 1970, before many other state and federal environmental laws, and it was done in response to what Republican Gov. Dean Davis saw as unchecked development, primarily around ski area resorts in southern Vermont. So, the plan Davis and others came up with was to have major projects reviewed by nine local district environmental commissions. And these citizen-based panels were supposed to make sure the projects comply with 10 environmental and social criteria outlined in the law, and these would be things like impacts on water quality, traffic, town services and the like.” Act 250 was further expanded in 1973 and several other times after that as well.

Act 250 applies to any housing development with more than 10 units and imposes a whole host of regulatory requirements. Any new housing construction project that falls under Act 250 has to go before a regional planning commission staffed by citizen volunteers who are often quite skeptical of any new development. These commissions can often take a long time to make their decisions on whether a project is approved or not. That adds costs. It has to be evaluated along ten different criteria and can be rejected for persnickety reasons under any of them. That adds delays and costs. There are site-specific reviews which make it difficult to know with certainty whether a project will get approved or not. That makes it hard to plan and hard to get financing, and so that adds costs. Act 250 means that developers have to get more permits at more levels of governments. That adds costs and delays.

What Act 250 does in practice is hugely constrain the scale, speed, and cost-effectiveness of new housing developments. Because developers cannot build at scale, it makes it hard to economize on costs. They then get all of these added regulatory compliance costs and so the only real option is to pass those costs onto the buyer. In other words, and as is a running theme in this topic, all of the benefits of the anti-development rules go to those who are already homeowners and already here and don’t want to see new development ‘in their backyard’ while all of the costs get shouldered by newcomers and those who do not already own homes.

In other parts of the country, with some relatively basic paperwork, a developer can buy a field, clear it, build dozens of homes at more or less the same time and do it based on a limited number of floor plans. They save a ton on costs, there is pretty low timing uncertainty since nothing is holding them up, and so then the developer can sell those homes at pretty low prices. Scale makes the prices come down. This is how working-class people afford homes. This is how my parents were able to buy a home. We lived in a mobile home until I was in the fifth grade when my parents were able to buy a house for $140,000, what would today be about $254,000. It was that cheap because the developer was able to build at scale and was not being garroted with green tape.

Some Vermonters want to act as if all these increased costs don’t cause real world harms, but they do. There is always a tradeoff. These increased costs are a huge part of the explanation for why housing is so much more expensive here than other comparable places. That has enormous costs for middle class and working class people. Some of those people also look down their nose at the way some other states allow development, but the big payoff to that is that working class and middle-class people can afford nice homes. At least to me, that’s worth more than a bobolink habitat. Of course, if you already own your home and have owned it for many years and you enjoy walking through the bobolink habitat, the working class houses that you blocked are an inconvenience that you’d probably rather not think about, especially as you pat yourself on the back for being so ‘progressive.’

Not only does Act 250 constrain scale, it empowers anyone who wants to delay or block development. To give just a couple of examples, neighbors used to it block a 71-unit apartment building next to the University of Vermont Medical Center in Burlington for seven years. The apartment building was going to be in one the most dense job areas anywhere in the state, was already in a developed area, and some NIMBYs were able to use Act 250 to hold it up for seven years. Act 250 can even block some of the most modest housing proposals you can think of. In West Windsor, a five unit project where each unit would be a mere 500 square feet was blocked by Act 250 because the land it was set to be on was a “river corridor.” The real estate agent that I am working with told me that on a one house project that he was a part of, a neighbor was able to hold up the project for more than a year by repeatedly claiming, without evidence, to have seen a bobcat on the property. Act 250, as it was designed to do, puts a huge weight on the scales against development and it has done so more and more over time as it has been ratcheted up. It’s not the only factor in Vermont’s housing crisis, but it’s a big one.

Local Zoning Creates Still More Hurdles

Meanwhile, local zoning only adds to the difficulty of development. In 2015 in Hinesburg, a fire damaged an apartment in a four unit building from the 1850s but because of zoning rules, they weren’t allowed to even rebuild it as it was, as Alex Weinhagen, Hinesburg's town planner said "You know there's something wrong with your zoning when you can't permit the very same thing you already have." Between density restrictions, parking requirements, setbacks, and other regulatory barriers, it can be near impossible in some places to build any new housing if any neighbors don’t want that. Seven Days, one of Vermont’s best publications, put together a truly remarkable 12-part series on Vermont’s housing crisis. Here’s an excerpt from one of them that is emblematic of this problem:

“the fate of a proposed housing project often depends less on a town's zoning codes than on the community's willingness to accept what might be allowed. "What it often boils down to is this very broad idea of compatibility with the neighborhood," said Owens of Evernorth, one of the developers behind the long-delayed Safford Commons project. And even as everyone professes to agree on the need for housing, the minutiae of zoning and Act 250 — the parking space allotments, the conservation requirements, the stormwater management plan — offer plenty of mechanisms to stall a project indefinitely. In December, Twin Pines Housing, the other nonprofit developer who worked on Safford Commons, submitted an application to the Hartford Planning Commission for an 18-unit affordable housing project on a parcel of land that belongs to St. Paul's Episcopal Church, just off Route 5 in the village of White River Junction. On the same parcel, Upper Valley Haven, a nonprofit that serves the homeless, plans to develop a 20-bed emergency shelter. The local zoning in that area would permit up to 14 housing units, according to Hartford planning director Lori Hirshfield. To build 18 apartments, Twin Pines had to apply for a special permit. The developers have to demonstrate that the project would provide the community an added benefit, explained Hirshfield — for instance, through outstanding building design or ecological stewardship. During the February 14 hearing, one planning commission member said he was troubled by how an 18-unit affordable housing development, combined with a homeless shelter, might impact the "character of the area," according to the meeting minutes. Another member noted that she had received lots of comments from residents who were "concerned with safety." Andrew Winter, the executive director of Twin Pines Housing , assured the commission that the Upper Valley Haven shelter next door would be staffed 24-7. Other commission members suggested that the design of the apartment building, which featured a flat roof, would be out of sync with the surroundings, and that a pitched roof might be more appropriate. Several Hartford residents also voiced objections; one said she understood the need for more affordable housing but that she no longer felt safe in her neighborhood. After some deliberation, the commission determined that Twin Pines' proposal didn't sufficiently preserve trees and other natural resources, nor did it "create a more desirable environment." They unanimously denied the application.”

This isn’t the end of it. Developers also point out that the permitting process keeps taking longer and longer than it used to and that municipalities, which usually lack any kind of expertise in wetlands designations, often add extra, cumbersome, development-hostile wetlands regulations. This too adds costs to any new housing, further driving up how much people have to pay for housing. They also talk about the ways in which all of these regulations drive up costs and force them to reduce the amount of housing they build. One realtor explained: “Often a developer ends up agreeing to things that some neighbor or DRB member wants even though the regulations don’t require it. More often than not, the developer accepts these one-off terms to reduce risk and delay. It’s a form of extortion. Reducing units is an example.” Austin Davis of the Lake Champlain Chamber of Commerce points out that these tactics have a huge chilling effect on development, saying ““How many projects aren’t done at all because potential developers are scared off before the process even starts? I’ve talked with people who back out as soon as they hear about the complexity and length of time the process will likely take.” Even the Sierra Club thinks Vermont’s anti-development politics are over-the-top and NIMBYistic. Even people who like Vermont’s tradition of hyper-localism accept that it’s susceptible to being leveraged by small groups who don’t want change. Ted Brady, the executive director of the Vermont League of Cities & Towns, acknowledged that “You get some people together, they don’t like the color of the house, they don’t like the color of the person moving into that housing … and time after time, you see lost opportunity in the number of units. Obviously, the process is to blame for a lot of housing not being developed.”

What About Burlington?

You may be asking, “well if all of these environmental regulations blocked new housing in the countryside, what about Burlington?” What about building up there instead of building out elsewhere? No luck there either. Burlington adopted a whole range of density limits to keep large parts of the city de facto single family homes. They instituted height restrictions near the University of Vermont campus. In 1990, Burlington was the first municipality in the nation to adopt inclusionary zoning and did so at a very high rate of 15-25%. Inclusionary zoning sounds nice in theory. It says, essentially, that if a developer wants to build new housing at the market rate, they have to set aside 15-25% as subsidized below the market price. The problem is that this eats into the developer’s profit margin a lot. Now maybe you think “I don’t care, I don’t like developers anyway so if they make less profit that’s fine by me.” Well, you should care. No state, and certainly not one as small as Vermont, runs its own construction company. Private-sector developers are who build housing in a market-based society. If you squeeze their margins down to zero, as inclusionary zoning can easily do if it is set this high, they will simply choose not to build the housing at all. Why would they? Why would any developer start a project that there’s a good chance they take a loss on? That’s what happened in Burlington. Let’s talk a look at housing construction in Burlington since 1990 and let’s compare it to the most famously anti-housing city in America, San Francisco.

That’s right. For most of the period since it adopted its inclusionary zoning rules, Burlington has built less than even the most famously housing-averse city in the country. The Burlington/South Burlington area has also built less than comparable metro areas.

It’s important to recognize that, like other Vermont regulations, inclusionary zoning doesn’t add costs for existing homeowners. It gives them a benefit, which is the opportunity to do virtue signaling, while the costs fall on newcomers and developers. Again and again in Vermont, the political pattern is for longtime residents and current homeowners to say “we want X, Y, and Z things, and we don’t want any of the costs of X, Y, and Z to fall on us so let’s make sure that those costs fall on developers and newcomers.” What that means though is that Vermont gets a lot less of two things it desperately needs- new housing and young in-migrants.

At least there’s some construction going on in the Burlington/South Burlington area though, however slow and insufficient. Other towns in Chittenden County (and Middlebury) are actually even worse. All of these places have demand for more housing, but they won’t allow the supply to expand. Look at the Y-axis on the chart above and the one below. The amount of development these Vermont towns are allowing is functionally zero.

On a certain level, it’s actually baffling because some of these places are slipping into decline. In the town of Middlebury, businesses struggle to survive because they don’t have enough customers and cannot find workers. Both of those are directly related to the fact that there is almost no reasonably priced housing anywhere in the area. The downtown area is hanging by a thread economically. You would think it would prompt the locals to relax an inch on the anti-development politics and allow some new housing development in one or more of the many open fields surrounding the town, but as best I can tell, they haven’t and they won’t. When Middlebury College, one of the most self-consciously progressive colleges in the country, wanted to put up solar panels to reduce its carbon emissions and fight climate change, it had an absolute bear of a time getting that approved because of local opposition to literally anything new. I understand that people don’t want to pave the Green Mountain National Forest or the Breadloaf Wilderness and I am with them on that, but must every square inch of open land be treated as if it is the Amazon rainforest?

One of the other challenges is that if you try to persuade Vermonters that we need more development, some of them will immediately say something to the effect that they don’t want Vermont to be New Jersey. I don’t know who is printing the brochure that teaches people to say that because it’s a made-up worry. Vermont has a population density of 68 people per square mile, one of lowest state population densities east of the Mississippi River. By contrast, New Jersey’s is more than 15 times greater at 1,211 people per square mile. If, by some miracle, we expanded our housing supply sufficiently and grew our population by 10% we’d have about the same density as West Virginia. We could literally double the population of this state and still be less dense than Tennessee. This is a super rural state and even if we got a slightly less rural……we’d still be quite rural. Even with slightly more housing, Vermont will still have a very rural vibe. That’s not changing. That’s even more apparent if we break it out by county. Chittenden County, where Burlington is, is by far the densest Vermont county at 99 pop/sq. mile (about the same as Alabama). All of the other counties except Essex County are between 33 and 14 (think New Mexico to Kansas level densities).

Act 60 Education Funding- The Great Idea With Unfortunate Side Effects

One of the ways that Vermont is weird but in a great way is the way it does education funding. There’s a very good episode of The Impact podcast with Sarah Kliff on this that starts out by describing the town of Whiting’s efforts to preserve its school. Alone among the 50 states Vermont does not do education funding on a local level, it’s statewide. When you pay your property tax here, it’s split in two. Part of it goes to the town for all of the non-education services, but the education part of it goes into one big statewide pot and then the state redistributes it to all of the towns. The reason they do this is because there used to be huge disparities in property tax revenue from one town to the next, often but not always based on who was next to a ski resort and who wasn’t. The towns that were flush with cash were known as “Gold Towns.” They had tons of money for their schools. Just a few miles away, another town with more or less the same kinds of people in it, would be constantly broke. This, understandably, offended Vermonters’ egalitarian sensibilities. So, in 1997, Vermont passed Act 60 which created that whole statewide funding system. In many ways it’s great! Schools here do not tend to vary in quality nearly as much as they do elsewhere. Moreover, just at a basic values level, this is worth defending and supporting. But, because there’s always a tradeoff in political economy, it does have four drawbacks. The first is that because towns are not actually having to directly foot the bill for their school, there is less local pressure to control costs. Second, and relatedly, in the places in the state that are shrinking and thus have schools that are way under capacity, because the towns aren’t having to foot the bill and because the school is often one of the last real civic things the town has, they understandably fight like mad to keep it open. Third, because the towns that are growing don’t really get to keep the education-related property tax money that comes with more development, they have a hard time funding school expansions to accommodate the growth in enrollment, and so their schools end up overcrowded. So, you end with some schools way under-capacity but it’s very difficult to close them, and some schools that are overcrowded but it’s very difficult to expand them. What makes matters worse is that the schools that are shrinking are in some of the poorer areas of the state while the schools that need to be expanded are in the some of the more prosperous areas, and that sits directly on top of Vermont’s Chittenden County versus everywhere else political divide, so trying to rejigger the education funding is fraught, to put it mildly. Fourth, and this is where it gets back to housing, because a town that allows new development will have more kids in its schools but won’t have the full property tax benefit from new housing, this makes some people who would otherwise be okay with new housing wary of it. For people in the middle who are neither NIMBY nor YIMBY, it tilts the scales against development. So stack that on top of all of the other factors weighing against development.

I think the proper response here is for the state to guarantee increased funding for any school that needs expanding. But admittedly that money has to come from somewhere and finding that money is hard in a context in which the state’s budget is shrinking because the population is stagnating and aging. The snake is sort of eating its tail on this one. Another problem is that many of the towns that don’t want to lose their school also don’t want to allow any new housing that might bring new young families in. Just 7 miles from the Whiting Elementary school, a small-scale developer wanted to build a walkable, traditional New England village of 19 homes at a range of price points….and the people of the town almost universally told him to buzz off; after stiff local opposition and numerous delays, the developer ultimately abandoned the project. Governor Scott noted last year that there are now 30,000 fewer children in Vermont’s schools than it did 20 years ago. In Vermont, as nationally, there is a lot of talk about urban-rural divides and the plight of small places but, at least in Vermont, some of those small, decaying places are that way because they refuse to allow literally any new growth. What do you do with that? I don’t want to be rude but it’s hard to help people and places this committed to not helping themselves if that comes with even the most microscopically smallest amount of change.

Single Family Homes for Me but Not for Thee

At the other end of Vermont’s income spectrum sits South Burlington’s Southeast Quadrant, otherwise known as the SEQ. Were the SEQ its own town, it would be Vermont’s richest with a median income over $140,000. There is probably no corner of this state that makes more sense to develop than South Burlington’s SEQ, but many of the current, often deep-pocketed, residents don’t want that. What they want is rural picturesque from their back deck but still be five minutes to Trader Joe’s. Even though they live within two to three miles of the biggest concentration of jobs and amenities anywhere in the state, they still think it’s their prerogative to block any development that they don’t want to see, at whatever cost to the state, to young families, to newcomers, and to middle class people. The first Twitter thread that I wrote on Vermont housing that got a decent bit of attention was on how these residents blocked a new 155 house development. One of the people who fought to block that housing is a guy who was a JP Morgan Chase executive in their tax planning division and retired here. I won’t give his name or address because I don’t believe in doxing people, but he bought a house that’s now worth approximately $2 million and that’s right next to the field this development would have gone in. That guy is now running for an open South Burlington City Council and continues to brag about how he helped block that housing.

Ok, so let’s make sure we understand how this series of events happened. A JP Morgan Chase executive retired to Vermont, bought an extremely nice house and that is very close to jobs and amenities, then slammed the door behind him as he blocked new housing, had the gall to say it was about the environment, brags about having blocked that new housing, and is now running for a City Council seat that he is likely to win because he defends the “change nothing, ever” preferences of the other NIMBY homeowners in the most affluent pocket of the entire state. This is who Vermont’s anti-development regulations serve in practice.

The City Council member who I quoted earlier as wanting to stop all new housing in South Burlington so that the town can try to do North Korean-style Juche in terms of food self-sufficiency lives across the street from that field. The elderly NIMBY who decried ‘ticky-tacky’ as well as two of the City Council members that voted for the onerous new anti-development regulations also live in the Southeast Quadrant. Other well-to-do retirees who live in the SEQ also spends their days fighting any new development near where they live on Golf Course Road and the Vermont National country club. Not only that but, at the behest of the SEQ residents, South Burlington has adopted intentionally onerous anti-development regulations and has tried to drive any new housing towards apartments and townhouses along the two main streets that are closest to Burlington and so already built up. So, the SEQ residents get their single-family homes but any new people without very deep pockets are going to have to make do with small apartments and no yards. How egalitarian. Lots of Vermont values going on there.

This is “single family home for me but not for thee.” They can dress it up in climate language all they want but there’s nothing virtuous about the self-serving hypocrisy of single-family home for me, small apartment for you because something something climate. Speaking of climate, when housing doesn’t get built in South Burlington, people have to drive from further away to get to their jobs and have to live in older housing that’s much less energy efficient. That’s quite obviously bad for the climate.

I’m sure that these are nice people in person, but the policies they are fighting for are actively harming young families and Vermont’s future. There is no part of this state where Vermont’s anti-development, anti-housing politics cause more harm or make less sense than South Burlington and its Southeast Quadrant. In my view, the state of Vermont should take zoning authority away from South Burlington so that it can upzone the Southeast Quadrant underneath these NIMBYs.

The nearby town of Shelburne is extremely similar in all of these regards. In fact, if it’s possible to be worse than the SEQ residents on this, they might just be able to do it. Not only does Shelburne adopt many of the same anti-development regulations as South Burlington, they even oppose development along the one major commercial road that runs through their town and that already has sewer and water infrastructure on the grounds that it would inconvenience turkey vultures. One of the opponents who considers the land it would be on, which is not land she herself owns, to be her “sanctuary” worried aloud, persumably while clutching the pearls round her neck, that having an apartment building nearby would lead to her Amazon packages being stolen. The median price of sold homes in Shelburne is just shy of $700,000.

Meanwhile, one housing project that received no opposition was a $10.8 million mansion on Governor’s Lane. Another town nearby, Hinesburg, has similar politics. When new housing developments were proposed there, "People just gasped," he said. "They said, 'That's not Hinesburg! That's South Burlington! I don't want Hinesburg to look like that!'"

Not Here, Not There, Not Anywhere

In totality then, Vermont’s towns have collectively construed what sounds like an absurd Dr. Seuss book. We can’t build in the rural areas. We can’t build new suburbs. We can’t build in urban areas. We can’t build here. We can’t build there. We can’t build anywhere. In this neighborhood, they worry about runoff to Lake Champlain. In that neighborhood, they don’t want new housing because they think it will cause gentrification. In this town, they oppose new housing because they call it sprawl. In that town, the oppose new housing because they don’t want developers to make a profit. This local zoning board doesn’t want outsiders. That local zoning board doesn’t want wetlands disturbed. The NIMBYs in this area want to exclude those below them on the income ladder. The NIMBYs in that area resent those above them on the income ladder. The environmentalists say no new housing if it hurts the worker bees (where the worker people are supposed to live is anyone’s guess). The climate activists say no to car culture. The woodchucks say no more flatlanders. And so the young people get fed up and leave.

This regulatory set up created a housing problem even before the pandemic. In 2016, employers in the Mad River Valley said that housing affordability was their number one workforce-related challenge. Even in 2019, Vermont Public Radio was asking “Why Does Vermont Have Such a Housing Crunch?” Then the pandemic came and with more newcomers, some of whom could now work remote, many others of whom were retiring early and cashing out equity in their homes in New Jersey and Massachusetts and New York and buying in Vermont. With supply as inelastic as it is, it only took a relatively small amount of increased demand to send prices soaring. According to the Vermont Realtors Association, the median sale price on a home in Vermont increased a mind-boggling 45 percent between May 2020 and May 2021. It then rose another 17 percent from 2021 to 2022. Roughly a year ago, a house came on the market on a Friday afternoon, the price was a little bit above what my wife and I could afford but not so far above that we couldn’t at least dream about it. The open house was at noon the next day. I went to it. There were nine cars there went I got there at 1pm. More than 30 viewers had already come by. Once I got to talk to the real estate agent, she informed me that the previous day, there were multiple all-cash, sight-unseen, waived inspection offers on the house (which was almost 100 years old) and at least two of the offers were well above the asking price. I could tell a lot of stories like this. Everyone who’s been trying to buy a home in this market and isn’t from legacy money could.

When a wave of new people come into an area, that local area has two basic options: it can either allow the housing supply to expand to accommodate those new people or it can stand by and watch as people get priced out. Because Vermont so adamantly refused to do the former, it is actively choosing to do the latter. The people who came during the pandemic with more money than us price us out of a house. We are pricing somebody out of the condo we are currently renting. Whoever would take our apartment if we weren’t in it is currently pricing someone out of that apartment. If we built more housing, you’d get more filtering and all of that would go in reverse. If we built hundreds of new houses, even at $600,000 a piece, that’s not something my family can afford but it means that someone who makes more than us can afford it. Then their house is open and it might be $500,000 so someone moves into that. Now that person’s $400,000 house is open. That’s something we can afford. So then we’d move out of the place we’re renting. That place would go to someone who makes a little less than we do. Their place would be open and so someone who makes a little less than they do would be able to take it, all the way on down the income spectrum.

Instead, for all the reasons I’ve covered here- anti-development politics, anti-capitalism, straight up NIMBYism, that isn’t allowed to happen and so none of that filtering occurs. Scarcity happens and so what little good housing there is goes for numbers that are eye-popping for a rural state. This is how a 2,200 square foot, four-bedroom house in Shelburne that was nice but nothing extravagant went for $935,000, which was nearly $100,000 more than the original asking price.

Sometimes, you’ll hear people blame AirBnB or people with second homes but, frankly, that’s just scapegoating. The problem is that we don’t build anything new. The other thing is that in some ways AirBnB and second homes are good for Vermont. Tourism is Vermont’s number one industry. We should want lots of tourists coming here. That’s how our state makes money. And seeing as we don’t allow much construction of new hotels, AirBnB’s are often where they stay. That’s good for the property owners and good for the state’s economy. The solution is not try to get rid of AirBnB’s but instead to build more housing. As far as vacation homes, those are good deals for Vermont’s taxpayers. The people who own vacation homes are paying property taxes but are using very little in the way of social services. We shouldn’t be mad about those either. The solution, the only solution, is to build more housing. There is no fixing Vermont’s housing crisis without building more new housing. Everything else is scapegoating.

More new housing is especially needed now because now interest rates are much higher and so every extra dollar in purchase price is a lot more burdensome for the cost of the mortgage and so, for first time buyers who need to finance most of the purchase cost of the house, Vermont’s higher prices are even more inflated over comparable states than they were just a few years ago.

Meanwhile, Vermont has a, more or less, volunteer legislature in which the pay is very low and so the people who can afford to do it are disproportionately independently wealthy and/or retirees. They’ve owned their homes for a long time. Housing unaffordability is not a problem they are well-positioned to see. At the same time, because the state makes construction so difficult, people with construction skills, for obvious reasons, leave the state. When I was a grad student in Boston, one of my best friends was a carpenter named Rob Campbell. He makes good money, as he should. In Boston, he has work whenever he wants it. In Vermont, he would be constantly in and out of work. Why on Earth would he move here? And if he somehow found himself here, why on Earth would he not leave? Why be a butcher in a state where they’ve made meat nearly illegal? What this means is that, even if we did want to allow a lot more housing to get built, we have a dearth of people who can do the building. We have just 15,000 construction workers in the whole state, fewer than we had in 2000, and 2,000 leave every year via retirement, changing jobs, or moving out of state.

None of this may be a problem for longtime residents who already own their own homes. They may think Vermont is defined by democracy, community, and environmentalism, but that’s not how it gets experienced by young families who want to buy a home and are priced out. To us, it’s not democracy, it’s NIMBYism; it’s not community, it’s “I got here first, finder’s keepers”, and it’s not environmentalism, it’s “I don’t like change and I don’t want to get criticized for that and this is my convenient excuse.”

What We Need to Do

So how do we solve this crisis? I think that some of the bills that the Vermont legislature is currently considering are good and important first steps. Limiting parking minimums, requiring towns to allow duplexes anywhere that would currently fit one house, and streamlining permitting are all laudatory and I hope they pass. But I still think they don’t go far enough.

First, we need to put it in towns’ best economic interest to allow new development. To do that, I propose that the property tax for any new housing that a town adds to its Grand List in 2023, 2024, 2025, 2026, 2027 goes entirely to the town. Currently, many citizens of a town can worry that new housing adds costs to the town but then the benefits are spread out. That means less incentive to allow new housing developments. This proposal flips that incentive. This proposal doesn’t tell towns what they must or mustn't do. A town that wants to maintain the status quo can. A town that wants to grow can now do that more confidently. We also need the state to pay for more sewer and water infrastructure for any town that wants to grow. The state could also give special funding or tax incentives for towns that adopt housing friendly by-right review rather than discretionary zoning, that shrink or eliminate minimum lot sizes, and that allow their housing stock to grow quickly. It is worth remembering just how much empty space we have to work with. In Chittenden County, we need at least 10,000 new homes. Let’s assume that, for whatever reason, Chittenden County wants those 10,000 new housing units to just be in and around Burlington and assume that this growth core includes Burlington, Winooski, South Burlington, Williston, Shelburne, Colchester, and Essex. That area currently has a little over 54,000 housing units and so a 10,000-unit increase is an 18.5 percent increase. Here’s what that looks like in terms of land usage.

Is all of that land usable? Of course not. But this shows just how much space we to work with. For each new home we need in Williston, we have 24 acres of space. Even in Burlington, space is often used in horrendously inefficient ways. The Champlain Farms gas station on Main Street should be an apartment building with dozens of units, not a gas station. The abandoned, blighted old YMCA building needs to be torn down and turned into apartments. It is entirely possible that the most valuable land in the whole state is One North Avenue. That’s currently not housing at all but rather the police station (this is not an anti-police point, merely that super valuable land should be used for housing that can generate lots of property tax revenue rather than for a non-revenue purpose). And for God in Heaven’s sake, we need to let a developer do something, anything with The Giant Pit in the middle of the city.

Here’s a representative sample of what this housing growth might look like for South Burlington. The Butler Way neighborhood off Route 116 is a just over 200 houses, including roads it’s about one acre each. The Dorset Commons apartment complex of just over 100 units on 8 acres total. The Dorset Farms neighborhood is about 200 units- mostly duplexes, some single family, on about 1/4 acre each. The Chelsea Circle/Foxcroft area is about 200 townhouses on about 20 acres. To get 1700 new units in South Burlington, we need more 2 Butler Ways, 3 more Dorset Commons, 3 more Dorset Farms, and 2 more Foxcroft/Chelsea Circle. That would use approximately 900 acres, in a town with more than 10,000 acres of space.

Special incentives, more funding, and begging are probably not going to be enough to persuade the areas NIMBYs to agree to this, but it’s what Vermont and its main metro area need. So, the state government should override local zoning in Burlington, South Burlington, and Shelburne and should issue an ultimatum to other towns in Chittenden County that if they do not allow their housing stock to growth 3 percent per year, they too may lose their zoning authority.

The time has passed to play nice with NIMBYs. In California, the rest of the state is in the process of overriding local prerogative in the towns that were the most NIMBY and refused to allow new housing. We can do that here. It’s worth noting that a number of California towns saw the writing on the wall as this was coming and decided to allow at least some new housing rather than lose their zoning authority. That would not be the worst outcome here either. If anti-development types decided to bend rather than get broken, that isn’t a bad thing.

Second, we need to reform Act 250. Personally, I would just get rid of it altogether. There are already lots of very good federal environmental protection laws that work just fine. We don’t need to be duplicating that, but I recognize that a clean repeal of Act 250 is probably a political non-starter in Vermont, so an acceptable compromise could be to raise the cap that it kicks in at from 10 to 50. That would help small-scale developers a lot. There are lots of 25-acre fields where we could have 49 house neighborhoods. That’s how lots of lots of other places ensure that people can find reasonably priced houses. Most people want that kind of housing. In a 2022 poll, 86 percent of Americans want to own their own home and, when asked “What is the ideal house you’d like to live in?” 89 percent of Americans picked a single family home. Opposing new suburbs is, in practice, imposing your preferences on the overwhelming majority of others. Moreover, while there are some places in Vermont that really seem to want to oppose literally any new housing anywhere, if a town wants to grow reforming Act 250 to having a 50-threshold instead of a 10-threshold would help them do that.

Third and finally, we need to convince Vermonters to embrace economic growth, enthusiasm for new housing, and a future-focused orientation. This is going to be the real sea change but, without it, Vermont’s future is grim. We could be a lively, energetic, thriving, fun place that’s affordable for everybody. We just need to build some more housing.

-GW