There are few words in political economy with more muddled meanings than ‘neoliberalism.’

As Paul Starr, editor of the American Prospect once quipped, “it’s an attempt to win an argument with an epithet.” But why is it an epithet at all? And why does it seem to have such a slippery definition? I think the answer to those two questions are linked: the term ‘neoliberalism’ conflates a wide variety of concepts that leftists dislike so, though that conflation irritates political economists who would rather be conceptually precise, it serves as a handy catch-all for leftists’ critiques of centrist liberals. The thing is though that the centrist liberals are correct and the leftists are wrong. Even the neoliberalism of the 1980s got much right, and today’s Neoliberal Project is better still. In short, neoliberalism is good and those of us who believe in a pro-market progressivism shouldn’t shy away from the label.

Unpacking the Term

The first way ‘neoliberalism’ gets used is as a perhaps intentionally vague way for the speaker to signal that they dislike economic inequality (which they associate with capitalism), individualism (which they see as cold and morally reprehensible), center-left moderate Democrats (who they blame for allegedly selling out the left via deregulation), and multinational corporations (which they see as exploitative). Though it is more useful conceptually to differentiate those four items- inequality, individualism, moderate Democrats, and multinational corporations- for left-wing populists and socialists, these four things are connected bulwarks holding back their political victory and stymieing the creation of what they see as a more economically just society.

A second related but separate way that ‘neoliberalism’ gets used by leftists is to denote a market-logic and government friendliness to markets where leftists think a market-logic is inappropriate and where they’d like to see the state act as a substitute for, rather than complement of, the market. This is often connected to- and one might also say conflated with- the policies in the United States and Britain in the late 1970s and early 1980s that trimmed the welfare state, promoted deregulation, weakened unions, and lowered taxes as a response to the economic troubles of the 1970s. This then gets further connected to leftists’ distaste for liberty and competition rhetorical frames in contrast to solidarity frames. David Harvey’s book “A Brief History of Neoliberalism”, which though I disagree with much of it I still think of as one of the better academic critiques of neoliberalism, advances most of its arguments along these line.

A third way neoliberalism gets used is to denote the movement toward less state intervention in markets in the developing world, particularly in Latin America and particularly with regards to the International Monetary Fund, the austerity-based loan conditionality it used, and the Washington Consensus- itself a package of ten policy prescriptions.

This is where much of the confusion over the term originates. For leftists, it is a word that makes sense because it links all four of the concepts in the first usage with the way it is understood in the second usage vis-à-vis the United States and Britain with the way that leftists believe it economically oppressed developing countries. But, for anyone who has a more measured or conflicted view about any of these arguments or who doesn’t consider those concepts to be tightly linked, the term shrouds more than it illuminates. When a speaker uses it, this kind of listener thinks “wait, what exactly are they talking about when they say neoliberalism? Do mean something from that first usage, or the second, or the third, or some combination? Do they have a precise concept in their head at all or are they just trying to win an argument with an epithet?”

Each of Those Neoliberalisms Gets Important Things Right, By The Way

The Washington Consensus

The root cause of Latin America’s economic troubles in the 1980s was not economists from the University of Chicago nor was it the IMF (even if most observers now agree that the IMF required too much austerity as a condition of financial assistance). The root cause was the bevy of imbalances created by decades of import-substitution industrialization (ISI) policies. In a nutshell, after World War II, many Latin American countries tried to industrialize by substituting away from imports and toward domestically-made products and so they imposed very large trade barriers to try to do that. As these countries moved into light manufacturing, things went fairly well. The domestic demand for such products was already there, the necessary technology was relatively simple and easy to acquire, and the goods were labor-intensive. During the 50s, 60s, and early 70s, growth across the region was strong, but then things got more difficult.

Critically, these ISI policies created some very significant imbalances. As these countries tried to move into more advanced manufacturing such as automobiles, they ran into problems. Because these producers were protected from foreign competition in their domestic market, they could get away with making shoddy, expensive products, which of course did not sell well abroad and so these countries did little exporting. This tempted them to overvalue their currencies but that just made their products even more uncompetitive on global markets and also hurt their exports of the agricultural products that they actually had solid comparative advantage in. Meanwhile, these states ended up subsidizing a lot of production and maintaining numerous state-owned enterprises. This meant that there were consistent budget deficits too, which led to unsustainable debt levels. Worse than that, these SOEs too often became corrupt, cronyistic resource maws parasitically leaching wealth away from the rest of society.

These imbalances finally exploded in the Latin American debt crisis that started in 1982. As part of their response to this debt crisis, the International Monetary Fund insisted on a raft of austerity measures as a condition for giving loans to Latin American countries. Admittedly, these austerity policies were a mistake, but it still remains the case that it was those imbalances generated by ISI, not the IMF-promoted austerity, that was the core cause of the problem.

So then let’s look at the Washington Consensus that was allegedly ‘imposed’ on Latin American countries, as well as others. This Washington Consensus, a term coined by the Peterson Institute’s John Williamson, was a set of ten policies that had widespread support in the 1980s and 1990s:

1) Avoid large budget deficits

2) Reduce specific subsidies in favor of pro-poor services like education and health care

3) Broaden and moderate the tax base

4) Have interest rates be market determined and small but positive

5) Competitive exchange rates

6) Trade liberalization

7) Liberalize Foreign Direct Investment

8) Privatize state-owned enterprises

9) Reduce market-restricting regulations

10) Secure property rights

On the whole, those are sensible recommendations.

Let’s take them in order of sensibility. First up, competitive exchange rates (#5). This, in the context of the Latin American debt crisis is a no-brainer. Even leftist scholars accept that, prior to the debt crisis, Latin American currencies were significantly over-valued. Secure property rights (#10) are foundational to properly functioning capitalist economies so that’s another easy one. Then, there’s trade liberalization (#6). On top of all of the other sound arguments for supporting free trade, it was the trade barriers inherent to ISI that had caused those big inefficiencies and imbalances in the first place, so an obvious way to not repeat the mistakes of ISI were to get rid of the protectionism. Meanwhile, East Asian countries were busy providing a model of export-oriented growth that did not rely on such market-distorting barriers. Reducing barriers to market entry (#9) and having market-based interest rates (#4) made a lot of sense too. A broad and moderate tax base (#3) is what most tax scholars recommend. Likewise, focusing on broad-based pro-poor policies over more narrowly directed subsidies (#2) remains a largely uncontroversial recommendation.

So, by my count, seven of the ten recommendations in the Washington Consensus remain well within political economy orthodoxy and, even taken collectively, do not come anywhere near the market fundamentalism that the Washington Consensus and neoliberalism more broadly are said to embody.

One can even make a good case for #7, liberalizing FDI regulations. That is after all how you attract investment in the first place; there is a reason we saw many states liberalize their FDI policies in this period. As far as #1, critics of austerity like Mark Blyth have shown quite thoroughly why it is so unhelpful and I have few if any qualms with his work, but large budget deficits did contribute to Latin America’s debt problems. As far as #8, privatizing the SOEs, the problem was not that such advice is unsound. Those SOEs were massively inefficient. The problem was that, the way those privatizations were conducted, the already-wealthy elites and well-connected cronies were able to purchase what had been public wealth for pennies on the dollar. That obviously worsened inequality and, particularly in combination with the austerity being taken too far and with the unavoidable adjustment that leaving behind ISI policies would entail and with the aftershocks of the debt crisis itself, set the seeds for the frustration and anger toward the IMF and neoliberalism. I want to emphasize here that as much as I think Latin American frustrations have been misdirected at the IMF and neoliberalism, those frustrations themselves were real and valid.

Still, it’s worth pointing out that the problems that the Washington Consensus and neoliberalism were said to have caused had little to do with eight of the ten recommendations and, even with regards to the other two, the problems were more about excessive or corrupt implementation rather than them being bad ideas in and of themselves. As Douglas Irwin, an eminent economist at Dartmouth has explained, the Washington Consensus policies have been a lot more effective than their populist alternatives.

Progressive Deregulation

It wasn’t just in the developing world where neoliberalism did a lot more good and a lot less harm than it’s given credit for. In the United States, excessive regulation really had gotten out of hand by the late 1970s. As Matthew Mitchell explained in LP #11, though it has mostly been forgotten for reasons of convenience, much of the deregulatory agenda that is now associated with Ronald Reagan actually began under Jimmy Carter, and that deregulatory agenda did a lot to safeguard the economic rights of the vulnerable while exposing protected insiders to market forces. A policy move today that would echo this kind of deregulation would be seriously reforming or, better still, abolishing the Jones Act, an antiquated maritime law that hurts Puerto Rico, undercuts the fight against climate change, and harms consumers (see LP #5, “The Progressive Case for Jones Act Reform” by Colin Grabow).

There are some modern echoes of that progressive deregulation in what is starting to be called “the abundance agenda.” The abundance agenda in essence argues that the problems normally associated with inequality are not first and foremost distribution problems but instead are problems where, for one reason or another, we have artificially-imposed scarcity and so the solution is not to get into ever more heated arguments over how to cut the cake but to remove the artificially imposed scarcity so that there’s an abundance of cake.

Housing is a big part of that. For an examination of the economic catastrophe that is Blue America’s bad housing policy, see LP #16: “Progressives’ Great Self-Sabotage: Anti-Capitalist Housing Policy.” Excessive occupational licensing artificially constrains people’s access to good employment and so it’s a good thing that, as Shoshana Weissmann explains, “occupational licensing reform is having a moment.” This kind of artificial scarcity, especially when combined with government subsidies creates what Daniel Takash, Steven Teles, and Samuel Hammond have termed “cost-disease socialism” in health care, high education, child care, and housing.

In addition to that abundance agenda, there are a lot of reasons for progressives to be friendlier to multinational corporations: small scale only makes sense in some sectors of the economy, consumers often love big business, corporations were not responsible for Trump’s worst excesses, they are not responsible for the increase in costs in core services like child care and housing, and they remain a positive contributor to American prosperity.

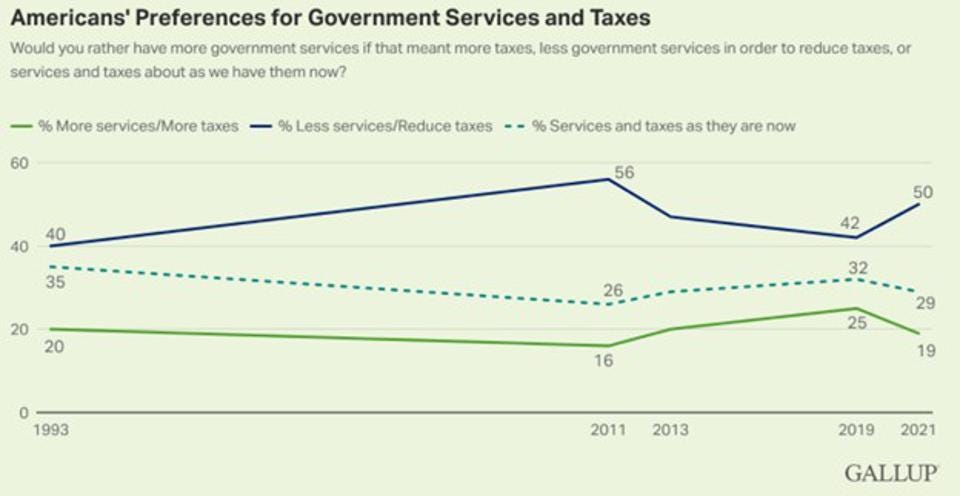

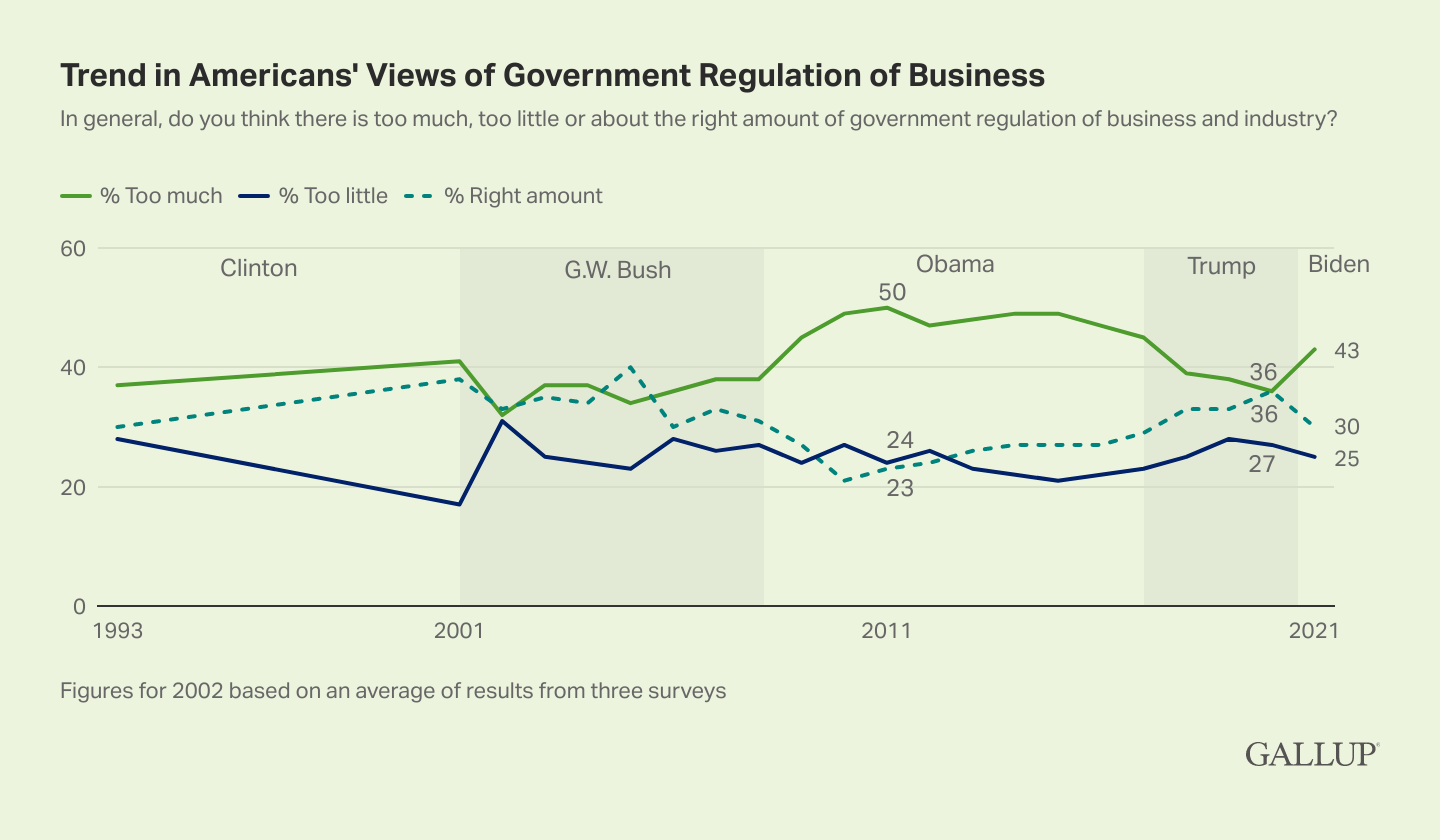

On a related note, rather than kvetching about neoliberalism, economic leftists in the United States need to square with the fact that their views are not in alignment with most Americans’. Since 1993, the American populace has consistently said that it wants lower taxes and fewer government services rather than higher taxes and more government services. Public opinion polling also consistently finds that many more Americans believe the federal government has too much power than too little and that more Americans think the government does too much regulating of business rather than too little. Note the consistency here despite massive changes in social attitudes over the time period covered in the polling charts. In short, though the American populace has been getting a lot more progressive on social issues, it has not been getting more economically leftist. One might even go so far as to say it has been getting more neoliberal, even if most poll respondents would not use that term.

The Neoliberal Project

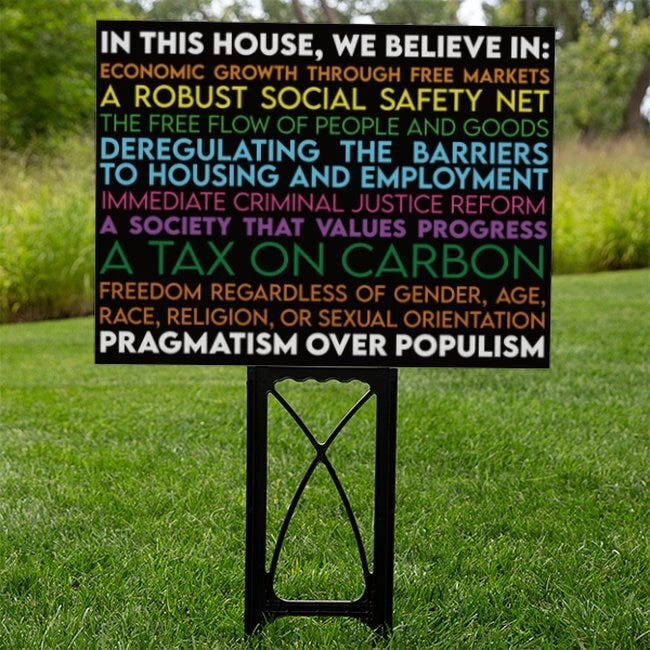

The final form of neoliberalism worth discussing is the Neoliberal Project. Perhaps a bit too appropriately, the best way to understand it is to take a look at the merchandise section of its website rather than the ‘about us’ section. In addition to a globe emoji, there are posters and stickers for abolishing zoning, building more housing, taco trucks on every corner, praise for the Federal Reserve, anti-populism, NAFTA, Jones Act reform, and this pretty awesome “What We Believe” yard sign.

It’s worth pointing out that this version of neoliberalism keeps much of what is most dynamic, most socially progressive, and most abundance agenda-oriented about the previous versions of neoliberalism while actively distancing itself from the market fundamentalism and welfare state opposition that fueled the opposition to the epithetical, caricatured images associated with those previous neoliberalisms. In other words, The Neoliberal Project is pretty great!

In sum then, it may be the case that neoliberalism gets used more as an epithet than anything else, but it still has a lot going for it. It may continue to conflate a range of ideas that might more accurately be conceptualized as separate rather than linked, but a lot of those concepts need defending anyway. And it may remain the case that few openly self-identify as neoliberal, but there is at least one person who does and he works in my office.